And so began the process of Shaya trying to re-create the tastes of Fenves’ happy prewar childhood, using recipes translated by Fenves from Hungarian that were not very specific and sometimes only included ingredients with no oven temperatures or measurements. The men have never met in person due to COVID-19, but with help from the museum they coordinated talks over Zoom and even did a Facebook Live where Fenves tasted the food of his childhood for the first time in over 75 years.

“The tastes, the smells, the very look of particular foods, trigger memories,” Hasia R. Diner, professor of American Jewish History at New York University told TODAY Food. “Perhaps more than any other aspect of culture, recollections of foods eaten take us all back to who we were, where we came from, what we have lost.”

“It’s been one of the most powerful and most important things I’ve done,” said the James Beard Award-winning chef. “Ever since I was a child, being able to cook for someone and have that translate into a happy moment, that was the one thing I felt like I could do. This was so much of a culmination of all of that. For me being able to rekindle positive prewar memories and talk to him about the foods that made him and his sister happy was incredible.”

Shaya made a special turkey recipe, which involved grinding the turkey meat and putting it back on the bone to bake, potato circles that Fenves said were reserved only for guests, not the kids, to eat and a walnut cake. Shaya knew he was tasked with an important job and wanted to make sure he got things right. He would send Fenves pictures of the food he made and ask for feedback. Fenves gave Shaya notes, for example that the semolina sticks he remembered should look like fish sticks — Shaya made sure to shape them correctly. Eventually, he sent Fenves food, packed in dry ice, for him to taste test.

“I was nervous, I didn’t want to change what the recipe was or make it in a way he wouldn’t recognize it,” Shaya said. “I’d ask questions, take pictures, he’d say, ‘No it looked more like this.’ I’d remake it, take more pictures, send it to him, finally he would say, ‘Yes, that it.'”

In some cases, Fenves said he remembered the recipes and that they brought back memories. Other foods, like a walnut crème cake Shaya re-created, he didn’t remember specifically, but told the chef that it was reminiscent of the many cakes and tortes he loved as a child.

“I would look for the expressions on his face,” Shaya said of observing Fenves trying the food, saying that he didn’t want to dig too deep into his memories out of respect.

After the recipe book’s long journey to America, Shaya said he is glad that it won’t just sit in a museum in a language that future generations of Fenves’ family do not read. “They are delicious recipes, I hate to think that after all that and having so much love for this artifact that it won’t be used,” he said. He said he plans to serve some of the recipes at his restaurants, Saba in New Orleans and Safta in Denver, for Passover this year.

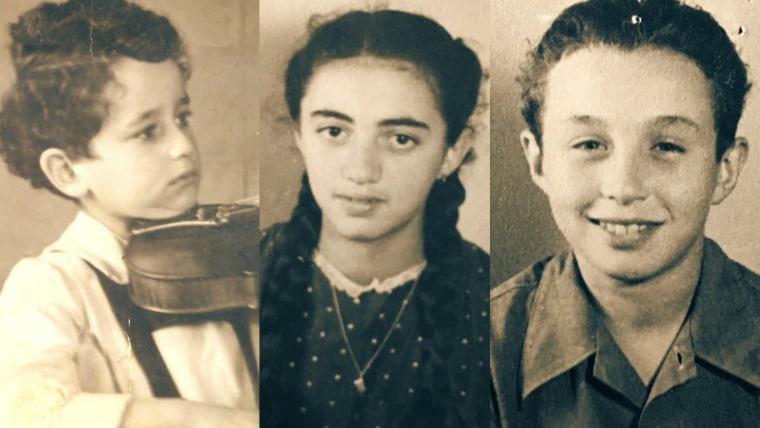

Shaya said that people have told him how moved they were by seeing their project come to life. “I’ve been getting notes from people describing their own family history and the Holocaust and how food played a role,” he said. “To Steven’s point, which I never considered, he’s spent his whole life talking about what happened during the war. He wants to talk about what happened before the war. They were a happy family with a lot of love and success and dreams. And that gets drowned out by the story of what happened in the camps or the ghettos.”

Professor Diner said that projects like the one that Shaya and Fenves embarked on are so significant, especially for women and men who lost their food cultures through trauma. “How important for them to then, in later years, be able to reflect back on life and food before displacement and dislocation and share those recollections of tastes taken away from them,” she said.

Shaya said he thought he achieved that with his cooking.

“I hope that I brought Steven and his family some sense of joy or a memory that is powerful for them.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/types-of-engagement-ring-settings-guide-2000-86f5b8f74d55494fa0eb043dee0de96e.jpg)

More Stories

Low Carb Gluten Free Apple Crisp

Vegetarian Shepherd’s Pie Recipe – Pinch of Yum

Our Favorite Broccoli Cheddar Soup